The recent call from Housing Now, a new alliance of business lobbyists, unions, academics and think-tankers, to solve the housing crisis with “thirty more Surry Hills” across Sydney made my ears prick up. For one thing, they were right – and one never expects to agree with orthodoxy. For another, I’d made the exact same proposal to then New South Wales planning minister Rob Stokes several years ago. “Just photocopy the plan of Surry Hills,” I’d said, “and stamp it out across Liverpool, Lakemba and Penrith. People there will enjoy it every bit as much as we do, and why not?”

He’d laughed, but I wasn’t joking. In the intervening decades, the imperative to limit sprawl has sharpened into a three-pronged crisis of affordability, sustainability and public health. But the solution remains. A Surry Hills mix of terrace housing, converted warehouses and the odd low-rise walk-up could hugely increase density while creating cool, walkable streets, decreasing morbidity, cleaning the air and building community. But God, as ever, is in the details. We have to get it right.

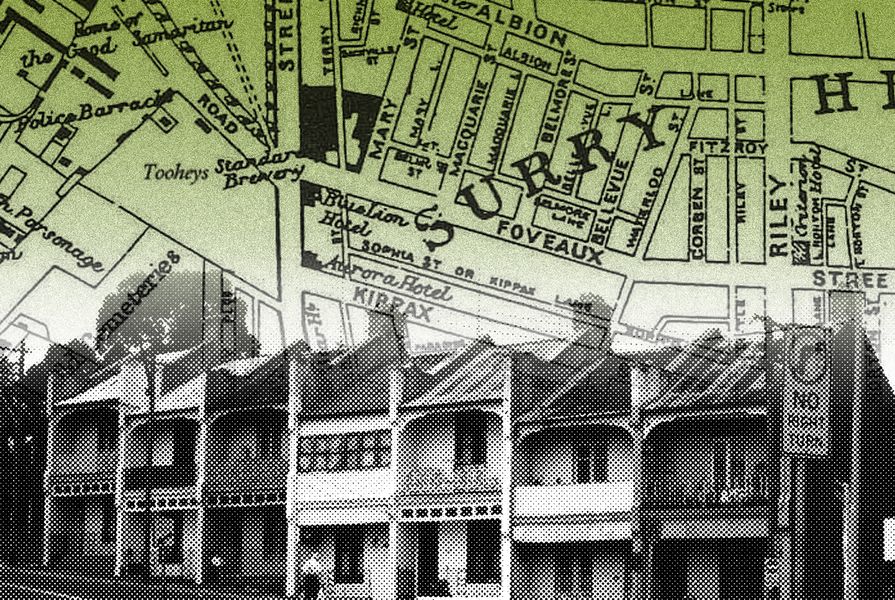

A hundred years ago, Surry Hills was a reeking slum. In 1890, with twice its current population, this 1.3-square-kilometre precinct to the city’s immediate south was characterized by rampant overcrowding, open sewers, deadly contagions, illegal brothels, backstreet abortions, opium dens, foul-smelling industry and violent razor gangs. The misspelling of England’s pastoral “Surrey” seemed symbolic. Surry Hills was a place from which many fantasized about escape. Now, with a median house price of $2 million, many more fantasize about buying in. This dramatic social change might suggest that the fabric itself is irrelevant. But in fact, the plans, sections and dimensions are critical to Surry Hills’ success, now and as a blueprint for the future.

Surry Hills is a grid of narrow streets, narrower lanes and yet-narrower houses, the slimmest of which is a mere 2.5 metres wide. Few dwellings have off-street parking, and when cars are parked on the streets, the remaining carriageway is often too narrow for passing. Similarly, many laneways are too narrow for rubbish trucks, let alone any sort of U-turn, and the square-tube house plan – often little more than 100 square metres – means you can often see right into your neighbours’ yard. Almost none of this would be allowed for houses being built today.

But all these constrictions are of the essence. Surry Hills succeeds not despite but because of them. The narrow streets enforce low vehicle speeds and decent manners. The narrow lanes require smaller, quieter rubbish trucks. And the constriction of private space encourages residents to spend more time in the public realm – in bars and cafes, parks and pools and shops and libraries. Further, the density – which, at just over 12,000 people per square kilometre, is almost 20 times that of a regular suburb like Penrith (546 people per square kilometre) – gives numbers sufficient to support local retail, parks and street vibrancy.

The sharing builds community, as private lawns, cinemas and pools consolidate into public ones. As to urban cooling, the terrace house works both in mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation arises through the long, narrow plan and shared party walls, which reduce external surface area per household and therefore limit heat transference. Meanwhile, the walkability afforded by density reduces vehicle dependence and enhances public health, as well as the viability of public transport.

This is all such a win-win that you’d wonder why it isn’t happening everywhere, in every city. In fact, cities such as London, with a long tradition of mid-rise medium-density housing, are doing a far better job of this – viz. the work of Peter Barber. But in Australian cities, where many still cling defiantly to that dullest and most exorbitant of housing forms, the Great Australian Dream, governments shy away. Politically, they think, it’s far easier to deliver massive up-zoning windfalls to a few friendly developers than to rezone for smaller gains (which necessitates some destruction) across the broader suburban landscape.

But consider our DNA. The traditional terraces that typify the whole of inner Sydney, and most of inner Melbourne, were built incrementally, by small builders, in twos, threes and fours. This, and the endless variation within a form, is part of the reason for their urban success. Within the serried subdivision, there are some decorated, some plain; some skewed, some straight; some with side walls like blinkers, some continuous; some with frontal parapets, some pedimented, some gabled; some with cast-iron columns, or gardens, or pavement-lit basements.

The variations are many, but the essential plan endures. And so does the underlying genius of the form – that is, its acknowledgement of both the individual and the collective. Each dwelling enjoys its own slice of earth and sky, while together they agglomerate into enjoyable streets and hoods.

The popular belief, endlessly repeated around the professional and academic traps, is that this varied uniformity – or uniform variety – manifests the nineteenth-century terrace-builders’ reliance on easily available pattern books. But I have hunted for these apocryphal pattern books, here and in the RIBA Library in London. And although I have found one or two, I’ve seen no evidence, written or anecdotal, that these patterns were widely used in Sydney.

More likely is that the houses arose from a combination of habit and constraint. Most of the builders, back then, would have either been British-trained or worked according to British standards. And – this is key – the subdivision of street-front land into ranks of narrow blocks (3–5 metres wide and 20–25 metres long) made any other form of development virtually impossible.

New South Wales never actually had a Building Act, but throughout the nineteenth century there were many Building Bills, which included verbatim reproduction of those parts of the London Building Acts that had evolved through the centuries after the Great Fire of 1666. These Acts, mandating street-to-house width and width-to-height ratios, requiring protruding party walls and, in London’s case, banning street-front timber architraves or balconies, essentially designed the Georgian terrace house.

It’s a reminder of the 1982 truism from theorist Jonathan Barnett that urban design is the art of designing not buildings, but the rules that shape them. This is a great wisdom, of the kind we could use more of in New South Wales, where even deliberate ministerial attempts to enable “the missing middle” – such as the so-called medium-density SEPP – fail because no-one got around to precluding the councils’ rights to demand setbacks and block subdivision.

Of course, relying on wise government implies the triumph of hope over experience. Still, we could indulge in a little auto-engineering. Even while Rome burns, we could usefully rethink the typology to create light-filled terrace-house patterns for ourselves, redesigning our own DNA for the coming polycentric, localist, slimmed-down century. Much to gain, I’d say, and little to lose but our waistlines.