REVIEW PETER SKINNER PHOTOGRAPHY PATRICK BINGHAM-HALL

Review

Suncorp Stadium – known as the “Cauldron” – seen across the South Plaza. The low hovering roof was designed to minimize light and sound spill.

Oblique view of the northern entry facade, with the timber-screened verandahs and restaurants behind.

The open and airy spaces of the restaurants.

The Caxton Street entry seen through the palm trees of the North Plaza.

The building steps back around J. H. Buckeridge’s 1895 Christ Church and memorial cemetery at its south-eastern corner.

The glazed elevation adjacent to the cemetery includes Jill Kinnear’s artwork The Veil.

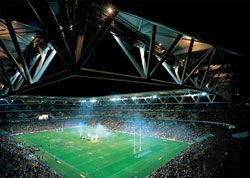

Night-time view of the dramatic yet intimate stadium.

The colours of the Broncos rugby league team are reflected in the stadium seating.

SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT IS an increasingly sophisticated and fluid global commodity, but what gives it real currency is its appeal to raw tribalism. Beyond technology, psychology and marketing, team sporting encounters are still fundamentally fuelled by a collective memory of past triumphs, injustices and enmities. The new Suncorp Stadium at Lang Park is the result of a successful architectural collaboration that draws together both the head and the heart of this sporting equation. For this project, the international stadium and urban design expertise of HOK Sport + Venue + Event has worked in association with PDT Architects, a practice with strong sporting links in Queensland.

We all crave belonging, and in the life of the city the football calendar unites citizens around the water cooler and provides a safely sanctioned outlet for collective passion.

But today, sporting engagements are as much about bread as they are about circuses.

Though Roy and H.G. spoof the rhetoric of “state against state, mate against mate”, sporting events and venues are real tools in the interstate battle for hearts, minds and dollars. Sports events stimulate tourism directly and indirectly by showcasing the character and attributes of the host city. In Brisbane today the dominant economic driver is not tourism, however, but long-term interstate population migration. Over a thousand people a week are persuaded to switch teams and relocate to South-east Queensland, and the resulting construction and property growth powers our economy.

While we cannot attribute this mass translocation to the superior appeal of the architecture (or sport) of Queensland, nor should we undervalue the very real contribution that major architectural projects make to the perceived culture and character of a city. At its best, architecture can build on and extend local patterns of urban engagement and understanding, underscore and celebrate the qualities of place, and reflect and valorize admirable local character traits and mores. From this regionalist viewpoint it is easy to understand the remarkable popular success of Suncorp Stadium.

Brisbane has a good oval stadium at the Gabba for the spatially diffuse spectacles of cricket and Australian Rules, but the city lacked an equivalent rectangular arena for the gladiatorial Rugby codes we call our own. In its search for a location for a new “Superstadium” the state government explored a number of large and well-serviced sites – the underused RNA showgrounds, a greenfield site by the airport and the disused Roma Street goods yard. In the best Queensland tradition, the final choice of Lang Park was a political call that combined parsimony, passion and pugnacity.

Functionally, the tight site at the junction of the suburbs of Petrie Terrace, Paddington and Milton was problematic. Surrounded by small residences, it is over the hill from the city, it lacks space for parking, and train stations, while nearby, are not immediately adjacent. From a cultural perspective, however, the choice was clear. The site was Brisbane’s principal burial ground till 1875, a local sporting recreation ground since 1891, the home of the Queensland Rugby League since 1954 and the venue for the State of Origin contest since 1980. This field at the bottom of a bowl of humble timber cottages is the traditional heartland of the working man’s game in Brisbane. The neighbours were long accustomed to the presence of the football ground and the serviceable if unexceptional western stand could be economically incorporated into the redevelopment scheme. Local pubs and restaurants benefit from the influx of fans and the big match pilgrimage down Caxton Street was legendary. If fans needed to be coaxed from their cars and introduced to an integrated public transport system en route to the game, could that be a bad thing for the city?

HOK Sport and PDT Architects’ strategy to re-energize Lang Park starts with the big people movements. It draws together a road overbridge and upgrading of pedestrian access to Milton railway station, a generous pedestrian plaza link over the busy Hale Street arterial and a twelve-bay bus station below podium as major arrival modes to the South Plaza entry. The North Plaza entry is more gently landscaped as it opens out to link with Caxton Street, the picturesque winding high street of the inner west suburbs.

Upgraded pedestrian routes from the city are currently pinched at Upper Roma Street, but the architects’ infrastructure master plan proposes a new pedestrian over-rail route through the historic Barracks precinct that will dramatically strengthen the functional and ceremonial links to the city.

Design reports describe the site strategy as “pavilion in a park”.While the metaphor is a bit folksy for an enterprise of this scale and robustness, it is true that by clipping the building’s territory tightly as a keep, the open plazas that provide compression and decompression zones at game time remain clearly in the public domain and provide generous suburban amenity year-round.

The architects’ shaping of the experience of arrival, entry and occupation of space in this building is effortless and masterful. The remarkably beneficial site topography allows a single plaza level to start on grade at Caxton Street and continue through to the plazas and walkways to Milton Road and Milton Station, while allowing bus and service access under from Castlemaine Street. The sectional design exploits this single plaza/concourse datum to stunning effect. As milling fans funnel through the single line of turnstiles that separate inside from out, within a few paces, they invariably halt in awe as the seating bowl drops away in front of them and they are enveloped in the vast floodlit stadium volume – the sacred turf stretched out before them and the goalposts seemingly touchable.

The excitement and immediacy of the arrival is sustained throughout the 52,500- seat stadium, hailed as the most intimate large rugby stadium in Australia. The colosseum geometry hugs the rectangular field with the closest seats a mere six metres from the touchline, and the furthest seats only fifty-five metres away. The low hovering roof has been designed to minimize light and sound spill and seems to amplify the simmering big-game intensity in the stadium they call the Cauldron. The roof itself is an elegant structure of four clear-span trusses (the longest 173 metres and 200 tonnes) with supports at the corners only. Resisting structural exhibitionism, the trusses are kept inboard to reduce overall building height and to simplify external elevations.

The difficult upper corners of the parallel-sided seating geometry have provided an opportunity to introduce standing bars that combine a bird’s-eye view of the field with the open-air tradition of “the outer” or “the hill”. These open corners celebrate the outdoor lifestyle and provide connections to older Brisbane landmarks – Robin Dods’ St Brigit’s Church, the arches of the Merivale Street Railway Bridge and the iconic Milton XXXX Brewery. The major function rooms also have a strong local character, exploiting veranda-like positioning above the entryways or, in the case of the impressive River Room, views back into the Petrie Terrace panorama.

The logistics of optimally seating, serving and servicing vast crowds in very short times are unquestionably complex, yet the stadium’s planning, structure and construction strategies are highly disciplined, simple and precise. The only time the design skips a beat is when it steps back around J.H. Buckeridge’s 1895 Christ Church and memorial cemetery at the south-east of the site. Jill Kinnear’s artwork The Veil on the adjacent elevation provides a slightly conciliatory gesture to the visually dwarfed and encircled timber church.

The architects have tackled a near impossible urban form problem: the enormous scale disjuncture between the two million cubic metre stadium and the adjacent precinct of some of the smallest, oldest and quaintest timber houses in Brisbane. The strategy of working down into the site topography and suppressing the roof structure limits the new stadium height to that of the pre-existing western stand. Floating the roof and articulating the elevations into functional sub-elements, each with its own material logic, achieves a further breakdown of the apparent mass. A carefully coordinated envelope strategy that utilizes naturally ventilated glazed corner bays, open mesh to stairwells, and fine screens of recycled hardwood battens outside the prestigious central function rooms successfully expresses lightness and airiness and gives a visual texture that graduates down to familiar scale as one approaches.

There is much to commend in Suncorp Stadium, from its respect for local traditions and rituals to its easy accommodation of the subtropical outdoor life. More than that, it embodies a particular set of character traits that are a source of pride and honour in Queensland sport, architecture and life. Like the legendary Lang Park heroes before it, Suncorp Stadium is neither flashy nor tricky, but its unpretentious candour belies an impassioned commitment to deliver disciplined and explosive performance on the big occasions.

PETER SKINNER IS HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND.

Project Credits

SUNCORP STADIUM, BRISBANE

Architect HOK Sport + Venue + Event in association with PDT Architects—project team Alastair Richardson, Mac Stirling, Paul Henry, Rod Sheard, John Brown, Chris Paterson, Alfred Laspina, Noel Park, Suzanne Bosanquet, David McCrea, Mike Tod, Luc Juoy, Matt Reynolds, Robin Deutschman, Matt Easton, David Johnston, Michael Flynn, Hugo Grozdanovic, Yohan Abhayaranthe, Stephan Heap, Daniel Volpato, Andrew Drummond, Lee Keogh, Ian Downing, Martin Barnes, Phil Wong, Ian King, Noel Edser, Ashley Munday, Richard Patenaude, Leon Gustavson, Richard Darvill, Nigel Harris, Natasha Vaz, Lucinda Thomson, David Matthews, Nanette Sanders, Colin Millwood, Melinda Lehman, Lora Leonard, James Dorrat, David McCrae, Michael Heath-Caldwell, Grant Cook. Client Major Sports Facilities Authority, Queensland Government— client representative Alan Patching. Project manager Project Services, Queensland Government. Civil and structural engineer Arup. Electrical engineer Connell Mott MacDonald (Connell Wagner), John Goss Electrical.

Mechanical engineer Connell Mott MacDonald, Triple M Mechanical Services (QLD), Sinclair Knight Merz. Hydraulic engineer McWilliam Consulting Engineers, Fairfield Plumbing, Connell Mott MacDonald. Landscape architects EDAW Gillespies, Wilson Landscape Architects. Lighting consultants Connell Mott MacDonald, John Goss Electrical, Thorn Sports Lighting, Sinclair Knight Merz, Norman Disney & Young. Acoustic consultants Bassett Acoustics, Hyder Consulting (Australia). Environmental consultants Sinclair Knight Merz. Quantity surveyors Davis Langdon Australia.

Communications Flack and Kurtz, Sinclair Knight Merz, GHD Group. Programming RCP (Resource Co-ordination Partnership). Builder Lang Park Redevelopment Joint Venture – Multiplex and Watpac Construction. Transport engineers Queensland Transport, Sinclair Knight Merz, Arup. Community liaison Elliott Whiting & Associates.

Catering Mike Driscall and Associates. Pitch Arup. Pitch (post-tender) Young Consulting Engineers. Fire engineer Lincolne Scott Consulting Engineers. Heritage architect Allom Lovell Architects. Access John Deshon Architect.

Way finding and signage Dot Dash. Building certifier Project Services, Queensland Government. Vertical transportation Norman Disney & Young.