Steve Mintern: On first look temporary concrete bollards seem pretty innocuous and it seems like a strange topic for a legal academic and a criminologist to collaborate on. Why bollards?

Tom Andrews: Peter and I were having a conversation about the risk of being run over from behind while riding bikes, at the time when there was an increase in car attacks that nominally fell under the heading of things done by people either directly or indirectly associated with Islamic State. What we had come to realize was that there was something theoretically similar in the way in which pedestrianization, roads, and city spaces seemed to produce this vulnerability. The starting point wasn’t bollards and securitization of public spaces, but rather, it was to rethink the political relations between different users of the everyday dimensions of the city if you start from a position of mutual but asymmetrical vulnerability, rather than harm.

Peter Chambers: Once we started looking at the bollards and doing some very early pieces around it for workshops. We asked “why are there these brutalist concrete cubes all throughout the city? What is the problem? Why is that problem a problem? What do they assuage? What and who do they address? Who or what did the bollards address, and how do they address their public and who or what are their publics?”

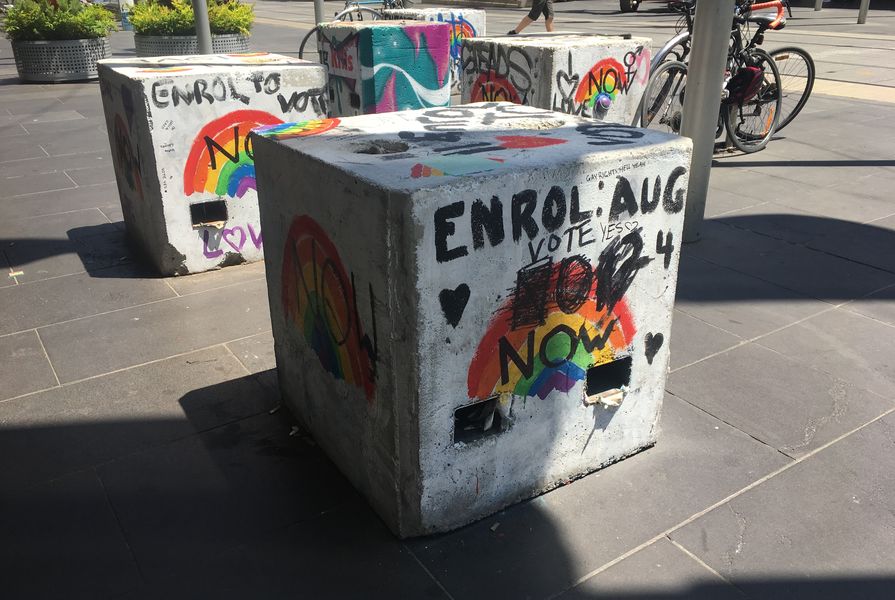

There are political and normative questions about public address and the publicness of spaces, putative publicness, how public are they are, etc. And then people’s attention drifted to “bollart.” Since the 1990s with cultural studies there’s definitely a reification of low level petty street forms of resistance insofar as if the government installs something and then you paint on it that resistance or contention demonstrates the presence of politics in the city. On the one hand you have bollards which demonstrate a securitization process, but don’t worry it’s okay everything in Melbourne is vibrant and interesting still because of street art. What was troubling for us was that, in a sense, bollart was precisely what removed the objectionability of the objects themselves. People have a problem with bollards, but you paint them pretty colors and then it just shows what a great city Melbourne is, and you can put it on Instagram.

SM: Is bollart a strong tactic of the weak, or a weak tactic of the weak?

TA: It’s a strong tactic of the strong. After all, it demonstrated the capacity for crochet to hijack a conversation about politics.

The main objection to bollards, as it was played out through the press, was that they’re ugly, and so the beautification practice was able to offset their incursion into the city. The most popular one was a Lego replica of the “I Heart New York” logo, which was, in two senses, a perfect lure. Firstly, it enabled the deflection of complaints into the aesthetic realm: “I don’t like them because they’re ugly; we shouldn’t have ugly things in the city.” Secondly, in terms of thinking critically the temptation – which we saw being given into – was to discuss the beautification rather than what was beautified.

PC: One thing that I wanted to add was that bollart conscripted the public into a securitization process, and in doing so it nullified any possibility of raising the contention that maybe securitization of urban space was precisely the problem. With the graffiti and street art it’s really about by public authorities saying “you may do this thing which is normally something which is transgressive”, and everyone thinks it’s great. But no, you’re part of a securitization process now. This points to the absence of politics in the polis.

SM: Talk us through what exactly the function of the temporary bollards is?

TA: The concrete cubes [that are used as temporary bollards] are not actually a specialized security device, instead they are counterweights for marquees at large corporate events, including the Cadel Evans Great Ocean Road cycling race, as well as iconically the Formula 1 Australian Grand Prix Road Race. These are multipurpose concrete cubes that have been repurposed as temporary security bollards. The kicker here is that according to some mechanical engineer’s estimations, if you were to run a small sedan into them at 40 kilometres an hour, the speed limit in the city, the bollard would slide along the bluestone paving of the Bourke Street Mall.

PC: One of the most perverse findings we came across was that this thing which was about reassuring the public that public space was safe to go shopping, objectively increased harm: it can become projectiles.

TA: There is a great series of photos, that the Commonwealth government’s security design contract published, of a blue 1990s Hyundai Excel hitting a similar but slightly different style of bollard. The car gets launched into the air and then the bollard shatters into fist sized chunks that get launched into the air.

PC: It’s circumstantial. Maybe they would slow down a Commodore and maybe they would slide, but you just have a different distribution of injury. It’s not addressing the problem. If the problem is children being run over and killed by crazy people in Commodores, the bollard doesn’t solve that problem, if that’s the design you’re looking for.

If you look at the location of the bollards, Fed Square, in front of the State Library and also at the corner of Southern Cross Station, they are located so tourists and especially tourists from regional Victoria get off the train when they come into the city and think “oh there’s bollards, we’re safe”. This instills the idea that there is a responsible government and they exist, and they’re responsive to our anxieties and look how they’re addressing them.

SM: So the bollards don’t keep people safe from car attacks, rather they are more concerned with confidence, whether that be in the government or their ability to shop at Zara, so work do they perform?

TA: Around the time of the Bourke Street attack in January 2017, a high level group of representatives from State, Territory, Commonwealth and New Zealand governments, along with representatives from the security services, and various police departments, met to produce a series of documents to deal with car attacks and other potential mass casualty incidents. The Australian and New Zealand Counter Terrorism Commission (ANZCTC) produced a series of reports outlining strategies. What’s really curious about the documents is the way in which that they describe the various responsibilities of different parties who have an interest in minimizing the risk of vehicular terrorism. The basic language that they use throughout these documents is the assertion:

Owners and operators of crowded places have the primary responsibility for protecting their sites, including a duty of care to take steps to protect people that work, use, or visit their site from a range of foreseeable threats, including terrorism.1

This the kind of phrase that seems really innocuous, but it picks up on principles of what we call in common law countries, tort law. Tort Law is about various forms of civil wrongs and first amongst them is negligence. The law reflects the proposition that basically if you can foresee that the conduct you engage in risks harming someone, then you owe that third person a duty to take proper care.

The byzantine way in which those legal relationships are structured is part and parcel of unpacking the distinction between public and private. But here, the ANZCTC simply says if you “own or operate a public space” – that means if people visit places that are under your effective control, you have the responsibility to minimize harm, and by saying that vehicular terrorism is foreseeable it then means that basically every private entity which is responsible for governing places accessible to the public, has the primary responsibility of performing the low-level environmental policing duties in order to protect the public from vehicular terror.

PC: So if the public was recruited aesthetically and semiotically into the securitisation process through bollart, corporations responsible for taking steps to address foreseeable risks are likewise recruited in a security assessment process.

TA: It reveals to us that there’s a public and a public: just because something appears to be “public” doesn’t necessarily mean that it is. Secondly that these kinds of regulations constitute different publics. Security somehow means that we can see the distinction between forms of public life a little more clearly.

PC: There’s an ontological distinction between the public and the private: that public space is something which is inalienable and which can be occupied, where in fact what most of the institutions at different of scales of government are dealing with is a conception of public space as something with differential mediated access, with competing, contesting publics who have varying claims to that space, and you have to balance the contesting interest between those different things.

What I really took from the temporary security bollards is it forces us to question both the categorical existence of public space as such, and also to think in a more processual way, to focus more on questions about how public space is constituted in each case. We think public space exists, but in fact it doesn’t, and maybe it never really did… For all of us, whether we’re urbanists, or architects, or people who are just concerned with public space, that’s really important. Our cherished object, public space, this thing that we accord value to, it might not be as we think it is, and might not even be, and that’s super interesting.

The Politics of Public Space: Public Lectures in Contentious Places is created by Office. The practice is running a crowd-funding campaign to print and produce a quarterly magazine to be launched at Melbourne Design Week 2020.